Artist Margit Czenki has started work on an unusual construction fence in Lörrach. Weaving together the local and the global, her subtle, yet gigantic work contains a secret message.

Since a couple of weeks inhabitants of Brombach, a suburb of Lörrach, can witness significant changes in the new territory of Schöpflin Foundation:

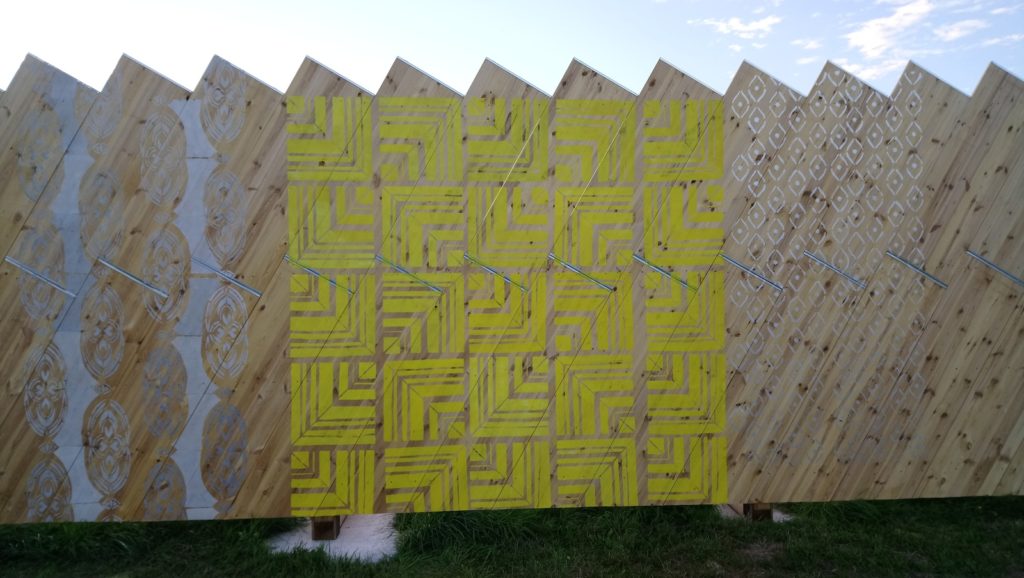

Quoting the shed roof design of the neighbouring factory, a fence has been built, that some people already call the most beautiful construction fence in Europe.

Carefully built, like a backdrop for a theatre play, the fence appears like a piece of faux-architecture. If you come closer, you can see tender patterns in silver and yellow tones, ornamenting the structure like a festive curtain.

„Starting in autumn, a sports hall will be built on the other side – on land, that the Schöpflin Stiftung is giving to the city for free as a long term lease.“ , says Christoph Schäfer, artistic director of FABRIC. „We need the construction fence to shield off the noise from the neighboring construction site.“

But a banal fence wouldn’t have been good enough for the ambitious project. „This is an art project – and a planning process at the same time. Everything functional is always also symbolic, an expression of some ideology or belief. We thus treat the construction fence with the same care, that we will give to other interventions and buildings in the process.“

Consequently Schäfer invited artist Margit Czenki to further work on the fence.

„The form of the fence designed by the FABRIC Team refers to the architecture of the factory next door. I wanted to show what happens inside.“ says Margit Czenki.

In the recent past, those factories produced cloth and textiles. The area around Lörrach, Basel and Mulhouse used to be a centre for spinning, weaving and for finishing techniques like sanforization. There were places for Indigo dyeing and the Schöpflin mail order Head Quarters. As most of the textiles worn in Europe are now being produced in Asia, most of these factories have left the Wiese-Valley. Only parts of Europes largest cloth printing facility, the high-tech KBC, are still in operation.

Surprisingly, there is another material being produced here. Not for domestic customers, however.

It is produced for a continent, that many don’t even see as a market today. It is a fabric exclusively sold to Africa.

„During my very first research in Lörrach, a company called Textilveredelung an der Wiese caught my attention, as they are doing the finishing for a very special cloth, the so called Afrikadamast.“ says Christoph Schäfer. „I was fascinated on the spot – and I knew, that we have to work with this. In fact, the african damask is responsible that we called our project FABRIC.“

Artist Margit Czenki came across the cloth during her residency at the Goethe Institute Dakar, in Senegal. In West-Africa, the fabric is called bazin.

„Locals pointed out to me, that the best bazin comes from Allemagne.“ Refering to the Made in Bangladesh labels one finds frequently in German High Street stores, Czenki adds: „Imagine my surprise ecountering cloth with golden Made in Germany labels stitched into it on street markets in Dakar. In the region, Germany is probably better known for the cloth, than for cars.“

In Europe, damask is known as a fine (and a bit old fashioned) material for tablecloth and napkins – the sort of stuff our grandparents only used on Sundays.

However, people in and from West-Africa wear this fabric – and favour it for it’s stiff crunchy feel and shine.

The cloth reportedly is woven in Europe, and finished in Lörrach. The white damask is then being exported to West-Africa.

Mali is most known for it’s dying capabilities. Women in Bamako, the capital, dye and process the fabric, before it is sold locally – and exported again to other cities and to West-African communities around the globe. Some of them are famous – and seen as stars by many customers of their colorful products. The final garment is sold for a price higher than a well made, hand-tailored suit.

„Hans Schöpflin has brought us into contact with American filmmaker Maureen Gosling and anthropologist Maxine Downs. They are working on a film on the Mali women.“, says Christoph Schäfer, who plans to invite the documentary film team to Lörrach at a later stage of the project. Their not yet finished film Bamako Chique: Threads of Power, Color and Culture focuses on the art and economy in Mali.

„In the early 1970s a group of Malian women dyers helped to re-invigorate the hand-dyed cloth industry throughout West Africa by producing a wider palate of vibrant colors and innovative designs, which continue to evolve even today. Their creative use of bright color-fast dyes and intricate patterns have turned hand-dyed bazin (an imported polished cotton) into popular fashion, sought after by rich and poor alike. Now a lucrative industry, hand-dyed cloth provides a sustainable source of asset building for many women.“ writes Gosling on her webpage. „By following the daily challenges of several Malian cloth dyers at different levels of economic attainment, we witness the power that women’s artistry and entrepreneurial skills have to express the universal human need for beauty, identity, and indeed, survival.“

„Usually we think, that in today’s economy, garments aren’t made in Germany anymore – besides some ecologically-sound fringe products. Making Afrikadamast a subject for the art-work and follow up research and projects, gives us the chance to change the perspective of how we look at production, trade, culture and the relationship between the global North and the global South.“ explains Christoph Schäfer. „It is a super-local theme and, at the same time, a super-international one.“

Meanwhile, Margit Czenki concentrates on the white shiny pre-product Fabrique en Allemagne.

Hundreds of jobs in Lörrach and Germany depend on the export of the fabric to West Africa.

The Afrikadamast is interwoven with patterns, that raise many questions, concerning aspects of economic and cultural exchange, of post- or neo-colonial relations, of appropriation and exploitation: How are these weaving patterns developed? Who designs them? Where are the designs made? How does the communication between Africa and Germany work?

While some of these questions might stay unanswered, thinking about the material challenges popular preconceptions of Africa-Europe relations.

Parts of the construction fence are already filled with stencil patterns. Margit Czenki decided to work with hand-cut stencils from paper, and with motives derived from the sometimes barely visible Afrikadmast-patterns. A conscious mistranslation of failed translations, or an appropriation of an exploitation – the patterns on the fence do not give away their origin too easy.

„I toned down the contrasts, because I want this work to be something of a background for the unfolding FABRIC project.“ Drawing a comparison to the world of music, Czenki adds: „I imagine my piece like a rolling bass track, that creates a basis for the tunes and lyrics by other artists and the people from Lörrach.“

Like a theater prop with a fake curtain, the construction-fence-as-ambient-artwork frames the land – and prepares the stage, where FABRIC’s production of desires can unfold in the years to come.

All other fotos in this article by Christoph Schäfer for FABRIC (c) 2017

[wds id=“3″]